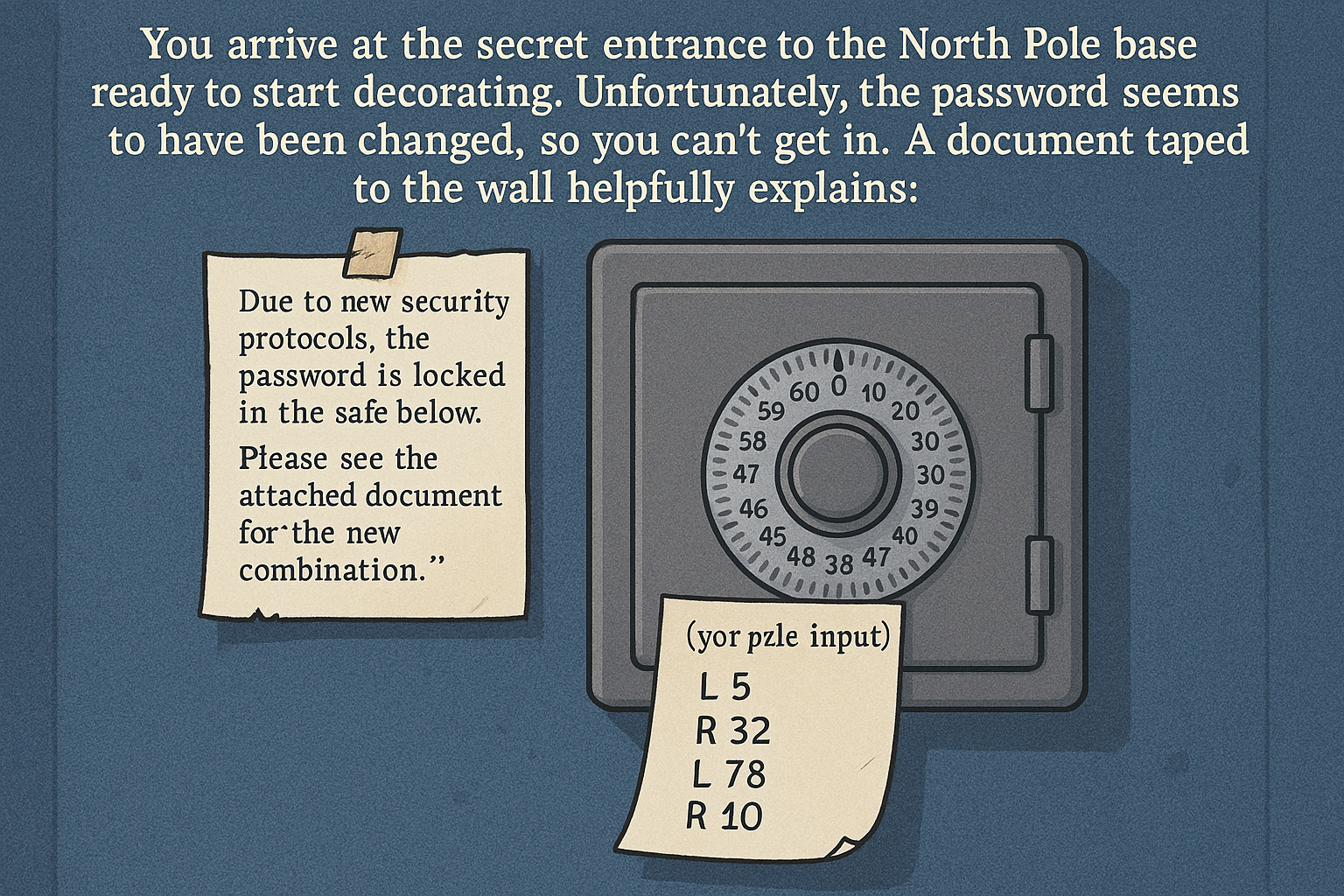

You arrive at the secret entrance to the North Pole base ready to start decorating. Unfortunately, the password seems to have been changed, so you can’t get in. A document taped to the wall helpfully explains:

“Due to new security protocols, the password is locked in the safe below. Please see the attached document for the new combination.”

Full source can be found: in GitHub

Part 1 solution

The safe’s dial is numbered from 0 to 99 and wraps around in both directions. Rotations are given as instructions such as L30 or R48, meaning the dial should be turned left or right by a specific number of clicks. The dial always starts at position 50.

The important detail is that the password is not the final dial position. Instead, it is the number of times the dial points at 0. In part one, this only counts when a rotation ends at zero. In part two, every click that passes through zero must be counted, even during a long rotation.

Representing Rotations

Each instruction is modelled using a Turn record:

1record Turn(char direction, int count) {

2 public static Turn parse(String line) {

3 return new Turn(line.charAt(0), Integer.parseInt(line.substring(1)));

4 }

5}

This keeps the direction and number of clicks together in a simple, immutable structure. A static parse method converts input lines like R48 into Turn objects.

To simplify calculations, the record provides helper methods that translate a rotation into a numeric adjustment. Right turns produce positive values, while left turns produce negative ones. The record also exposes how many full revolutions a turn makes around the dial and how many clicks remain afterward.

Reading the data

To read the exercise data into a list I can use later on the following method is added.

1@Override

2public void readInput() {

3 turns = inputLoader.splitOnNewLine()

4 .map(Turn::parse)

5 .toList();

6}

This method reads each line of the exercise and converts it into a Turn record.

Solving the equation

The first part is straightforward. Starting at position 50, each rotation is applied in full, wrapping around the dial using modulo arithmetic. After each rotation, the code checks whether the dial is exactly at position zero and increments a counter if it is.

First I add the following logic to the Turn record to actually compute the amount of ticks the number needs to move right. Keep in mind that if we turn left we essentially deduct the count as we make the number smaller.

1public long computeAddition() {

2 return direction == 'R' ? count : -count;

3}

Then it is just a matter of looping over all created Turn instances:

1long numberOfZero = 0;

2long startPos = 50L;

3for (var turn : turns) {

4 long turning = turn.computeAddition();

5 startPos += turning;

6 startPos %= 100;

7

8 if (startPos == 0) {

9 numberOfZero++;

10 }

11}

Part 2 solution

Since in part 2 we need to figure out all times that the number 0 is passed we need to update the logic a bit. Now we can already use the fact that some Turn instances may rotate the lock one full iteration. If we do this then all we need to do is focus on the remainder.

To achieve this I added the following methods to the Turn:

1public long numberOfFullIterations() {

2 return count / 100;

3}

4

5public long numberOfPartialIterations() {

6 return direction == 'R' ? count % 100 : -(count % 100);

7}

This can then be used to update the equation as follows:

1long numberPassing = 0;

2long startPos = 50L;

3for (var turn : turns) {

4 long partialIterations = turn.numberOfPartialIterations();

5

6 numberPassing += turn.numberOfFullIterations();

7

8 long updatedPos = startPos + partialIterations;

9 if (startPos != 0 && (updatedPos <= 0 || updatedPos >= 100)) {

10 numberPassing++;

11 }

12 startPos = computeNewPosition(updatedPos);

13}

Here I add the number of full rotations straight away to the count. Then we only need to look at the remainder to see if this rotates over the 0 position.